Urban Healing: Ethnobotany in the Bronx

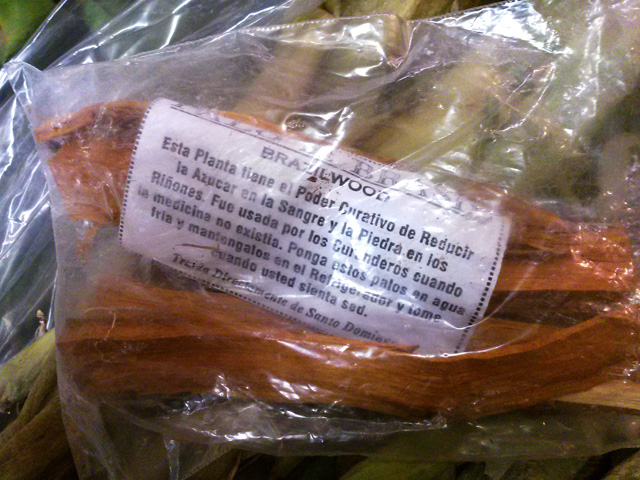

Brazilwood. The packaging says “This plant has curative powers to reduce the sugar in the blood and kidney stones.”

By Miamichelle Abad

Immigrants in New York City often do not seek out health care in hospital settings either because they fear the high costs or distrust the medical establishment. Instead, Latino and Caribbean immigrants may turn to home remedies and medicinal plants to treat illness.

The New York Botanical Garden has launched a project to bridge this gap between immigrant traditions and local doctors by teaching medical professionals about the home remedies used by these communities. The Cigna Foundation provided a World of Difference grant of $140,000 to the New York Botanical Garden that will fund the work of Dr. Ina Vandebroek, an ethnomedical researcher.

Dr. Vandebroek has done research on the medicinal plants used by Latino and Caribbean communities in New York and the role botanica shops play in these cultural healing traditions. Although botanica shops are well known for spiritual healing, they also carry the kinds of plants that Caribbean and Latino immigrants use to maintain their health.

Vandebroek says there’s a home remedy for just about any condition under the sun including health conditions like diabetes, arthritis and hypertension. Aloe Vera (called “sabila”), for example, is “the cure it all” for upper respiratory problems, diabetes, and skin problems, says Vandebroek. Some Dominican immigrants believe that plants with bitter properties burn sugar in the blood, making it an ideal remedy to treat diabetes.

Canelilla

Michelle Dominguez works at La 21 Division Botanica on the Grand Concourse and she says natural remedies “work much better than medicine,” because she believes there are fewer side effects. She can vouch from her own experience when she had the shingles. After following doctor’s orders for two days, she stopped taking the prescription medicine. “It made me feel dazed and out of it,” she said. Additionally, Dominguez says her mother has been controlling her diabetes with the help of Brazil wood (“palo de brasil”) instead of taking pills which she believes could cause kidney problems.

In a study Vandebroek conducted with Jeanette Rodriguez, a student from Columbia University, she found that 11 of 12 botanica shops they interviewed in the Bronx sold dry herbs (and nine of these also fresh herbs) for conditions such as arthritis, anxiety, depression, diabetes, kidney problems, infertility and headaches. She has cataloged over 200 plant species used by Dominicans during interviews with 175 immigrants in New York City.

For the cold season, orange plant leaves (“hojas de naranja), lemongrass (“limoncillo”), guanabana leaves and canelilla are the botanica’s bestsellers. Dominguez says that these ingredients boost the immune system, prevent sickness and relieve cold symptoms. Another remedy recipe calls for dragon leaves (“hojas de dragon”), Brazil wood, canelilla and orange plant leaves, to provide a natural jolt of energy, while also calming nervous or anxious people.

As the U.S. becomes more diverse, an increasing numbers of immigrants will practice their ethnobotanical traditions, even in urban areas with greater access to health care, says Vandebroek. The problem is that the doctor-patient relationship isn’t open enough to talk about what kinds of remedies a patient may be using along with or without modern medicine, she says. Dr. Vandebroek has started a training program that educates medical students and physicians on how to provide clinical care based on the understanding of how their patients use medicinal plants and their cultural beliefs about treatments.

Dragon leaves

Along with these trainings, she hopes to create a low-cost — or even free — app that would help patients talk about what remedies they use with their doctors. In order to strengthen the roots of ethnobotany in New York, Vandebroek suggests that more participation is needed from the medical community. “It is our hope for this to become more integrated in the curriculum at medical schools,” she says. “There is still so much to study about the use of plants as traditional medicines.” The ultimate goal, she says, is for the patient and doctor to have a mutual treatment plan that the patient is willing to follow.

Following her in-depth research and interviews with Latino and Caribbean immigrants, Vandebroek is drafting a Spanish language guidebook for the Caribbean community on common medicinal plants used by Dominicans in New York City. The guidebook will provide cultural and biomedical information on selected commonly known plants, along with their common Spanish name and their scientific identity.

The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden also has about 7.4 million specimens which visiting scholars can study on-site or borrow. Of these, 2.3 million have been digitized and are viewable at the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium.

Learn more at the Botanical Garden’s Project to Improve Immigrant Health Care.