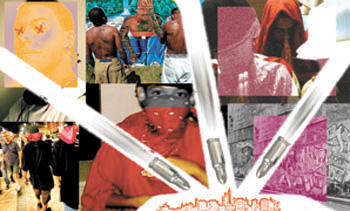

The War on Street Gangs

Gang Culture is a harsh reality in New York

Gang Culture is a harsh reality in New York

At first, the office looks conventional. The walls are all white and there are some computers on about 10 desks, each with old school-like wooden chairs. But soon you see a bulletin board with pencil-drawn mug sketches of “WANTED” criminals – and you realize this is no ordinary office.

You are at Gang Perp Central, in Harlem’s 25th police precinct – the place where they put all the bad boys away, where the restrooms lack paper and reek of nauseating smells, and where cops feel accomplished.

That’s where Sgt. Robin Lewis explains that gang violence is currently well-controlled and not seen as a threat to safety on city streets.

In other urban centers, gang wars are shedding blood and making national headlines. But in New York, cops say gangs are not usually involved in serious crimes.

“Gangs are usually involved with loitering and petty crimes; and are usually charged with misdemeanors, unless they get caught with knives or guns and have previous records,” Lewis said.

She said that blue-collar criminals and non-gang members are more likely to be involved with serious crimes, and that the city’s gang violence is typically limited to initiation rituals.

But, of course, there are exceptions. “Just last Friday, we had an incident with four Bloods robbing a local bodega on 116th Street. Over $1,000 was stolen from the cash register.”

That robbery sent the store manager to the intensive care unit at St. Luke’s Hospital in Manhattan. He had been stabbed in the chest and suffered from a punctured lung.

Lewis said witnesses spotted a group of young males, wearing solid-colored clothing, straying from the crime scene.

Nevertheless, Lewis and other law enforcement officers say the gang violence problem is not as grave in New York as in other parts of the country -– or as in New York in the past.

In fact, since the late 1990s the media has been reporting that West Coast gang members are met with a rude welcome when they come to New York.

“The gang situation in New York is under control,” Inspector William Tartaglia, head of the NYPD Gang Division, told New York Magazine.

In that report, Tartaglia said that –- when it comes to numbers, group loyalty and active criminality –- today’s gangs of New York are limp and demoralized, if not completely clueless. He said the gangs suffered a massive takedown in August of 1997, when scores of Kings and Queens were put away for long stretches, along with a loose array of Bloods wannabes and a smattering of members of new ethnic gangs.

Tartaglia said there are several thousand Latin Kings still spread throughout the five boroughs. However, members of that gang, composed mostly of young Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, have reportedly been relocating from New York to Chicago.

“Bloods are the main gang in Spanish Harlem, east of upper Manhattan.” Lewis said. “Bloods are usually outcasts with no family support, so they join these organizations with hope to fill a void and become accepted within a group … they’re lost souls, not a threat.”

Law enforcement takes credit for the demise of the Gangs of New York. Police officials say the NYPD’s 300-officer Gang Division deserves recognition for bringing gang violence under control by gathering intelligence from local detective squads, precinct cops, and informants. And by cracking down on gangs, when necessary.

According to published reports, in August 1997, New York City Police arrested 167 alleged members, in a three-day sweep called, “Operation Red Bandana.” The operation was reportedly designed “to break a pattern of violent crime, and to stop gang efforts to expand and organized in the city.”

It seems to have worked, at least partially.

Some observers point to other reasons that could have also contributed to the weakening of the city’s gangs, especially urban renewal. In the last three decades, many gang members were literally gentrified out of their turf.

“With the demand for drugs came corporate-style drug-selling organizations, and for young men in New York’s poorest areas, the lure of fast money quickly replaced neighborhood fealty and gang affiliation,” said Ric Curtis, an anthropology professor at John Jay College.

Curtis believes that the heroin epidemic of the seventies and the crack boom of the eighties actually weakened the ethnic street gangs. “So many neighborhoods were destroyed; there was nothing left to fight over,” he said.

Page designed by Adam Cox