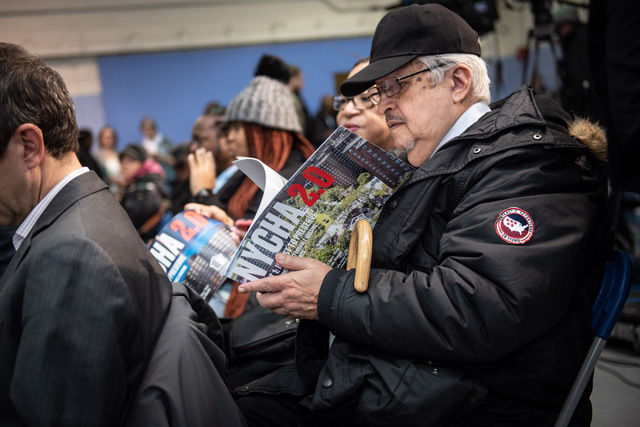

NYCHA 2.0

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced comprehensive plan to renovate NYCHA apartments and preserve public housing in New York City at the NYCHA Hope Gardens Community Center in Brooklyn on December 12, 2018. (Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

By Keith Lopez

It’s been a bad year for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Lack of heat and hot water are just two of the problems that plague NYCHA buildings. In January 2018, New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer announced that his office was launching a new audit of NYCHA heating systems. Stringer called it unacceptable that the city is failing to provide NYCHA tenants with heat in cold winters. A review of the Buildings Department’s annual compliance filings for high- and low-pressure boilers, showed that the rate of NYCHA’S defective boilers is “five times the citywide average, 39.5 percent of NYCHA inspections reported defects compared to 7.9 percent citywide.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio visits a heating plant at NYCHA’s Lower East Side Rehab Houses. Boys & Girls Republic Community Center, Manhattan. October 18, 2018. (Credit: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Tanesha Rivers, 44, a resident of NYCHA’s Chelsea-Elliot Houses, says reoccurring lack of heat and hot water is the most stressful part of living in a NYCHA complex. “Previously, I went to court complaining about the brown water or cold water or some days, no water,” said Rivers, who has lived in Chelsea for the last 13 years. She lives on the 11th floor of the complex “Now the heat sometimes, they put it up where it may be too high for the lower tenants, but it’s no heat for the higher tenants,” she said. “I have a friend that lives on the sixth, sometimes she may not get heat.” These issues she says, occur about once a week.

Chelsea-Elliot Houses

As recent as Thanksgiving, Rivers says the water pressure was low, then it went to cold, then it went to no water. “So people that were home for Thanksgiving, if they didn’t cook their dinner in a timely manner, probably say about 10, 12, there was no water after that,” she said. Rivers added that sometimes she uses plant water to wash her hands and face. She also doesn’t drink the water provided by NYCHA, but buys it instead.

There are times, Rivers says, when she is getting ready for work or school at 6 am and the water isn’t restored until after 8:30 am. She says she sometimes feels discouraged from going to school without a shower. “You shouldn’t have to feel like you’re living in a third-world country,” she said.

In April 2018, Governor Cuomo signed an executive order declaring that NYCHA is in a “state of emergency.” This executive order will provide the city with a $250 million investment. This additional $250 million will be added to the city commitment of $300 million, totaling $550 million. The funds are expected to help “expedite necessary repairs, upgrades, and construction, as well as address lead paint, mold, and other harmful environmental and safety hazards.”

In December 12, 2018, Mayor Bill de Blasio and NYCHA Interim Chair and CEO Stanley Brezenoff announced a plan, called “NYCHA 2.0,” which allows for $24 billion in vital repairs over 10 years. The city is launching three programs Build to Preserve, Transfer to Preserve, and Fix to Preserve. Build to Preserve will spend $2 million on new development on NYCHA land. Transfer to Preserve will use $1 billion for “capital repairs through the sale of unused development rights.” Fix to Preserve will address lack of heat, mold, lead paint, and rodents, while improving services and building maintenance.

According to the city, elevators throughout the NYCHA complexes are expected to be fully renovated by 2027. Installing door sweeps and rat slabs, along with 20 new exterminators, is expected to decrease the number of rodents by 25 percent by the end of 2019, and by 50 percent by the end of 2020. NYCHA will soon begin to test over 135,000 apartments that were built before 1978 for the presence of lead paint, with the goal of eliminating all by 2020. Roof repairs will be made with the goal of eliminating mold by 2026.