Corruption in College Sports: A Fight for Fairness

By Matthew Mallary

College sport is a multi-billion dollar a year industry. Division I sports teams have large TV contracts that provide universities and executives with six-figure salaries, while college athletes go unpaid for their labor. Student athletes are violating National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules if a coach buys them a hamburger. In addition to not being paid for their labor, they are not allowed to collect money from sponsorships or endorsements. This is particularly infuriating for those playing for high-ranked schools. Universities sell merchandise, like jerseys, that have player’s last name displayed prominently on the back.

The unintended result is cheating in many forms, and institutional corruption.

There are 460,000 players in the NCAA and the organization cannot catch everything. In the documentary “Foul Play: Paid In Mississippi,” sports fan and political commentator James Carville said, “There’s been cheating in college sports since the dawn of time.” It is true, not only in Division I, the pinnacle of college athletics, but also in Division III. Colleges are focused on winning and some will find a way to win, even if it includes bending the rules.

There is an assumption that the lack of money present in Division III would prevent this kind of cheating. Dr. Martin Zwiren is the head athletic director at Lehman College, which competes in Division III. Zwiren says that the majority of NCAA violations come from the astronomical sums of money in college sports, which incentivizes cheating, or what the NCAA considers cheating. “Coaches’ salaries are in the millions, administrators salaries are very high also, this means that there is a lot at stake for the higher-ups,” says Zwiren.

In 1964, NCAA Executive Director Walter Byers formulated the term “student-athlete.” It is supposed to convey “amateurism,” or the notion that college athletes are not professional, and therefore deserve no compensation for their exploits, other than a college education, room and board. The NCAA rules state that:

“College-bound and current student-athletes who want to compete at Division I and II schools need to preserve their eligibility by meeting NCAA amateurism requirements. If a college-bound student-athlete is paid for appearing in a commercial or receives an endorsement before he or she is accepted at an NCAA member school, his or her eligibility could be affected.”

Many student-athletes come from disadvantaged circumstances. They see sports as a gateway to a better future for themselves and their families. Some come from homes where it is a struggle to keep the lights or heat on. Schools know that money, or the potential to earn money, is going to be one of the main factors in decision making for the students.

This means that school may offer an athlete or that athlete’s family, a lump sum. This is usually done through an associate of the program, rather than someone with a direct link to the university. In addition to preventing student-athletes from collecting any money from sponsorships, the NCAA also prevents student-athletes from hiring agents. This means that athletes who are thinking about turning professional, are not able to plan for their futures.

The NCAA does not condone any sort of profiting off of an athlete’s image, including the sale of game-worn jerseys, autographs, and appearances. To many this seems a hypocritical stance for the NCAA to take, as the alleged “non-profit,” generated over a billion dollars in revenue. A study, The Price of Poverty in Big Time College Sport by the National College Players Association, found that 86 percent of student-athletes live below the poverty line. The same study also found that “The average out-of-pocket expenses for each full scholarship athlete (there are partial scholarships awarded in many NCAA sports) was approximately $3,222 per year during the 2010-11 school year.”

Since the competition between schools is so fierce, teams bend the rules. This is the case for schools that fall into NCAA Division I athletics. Division I is the highest level of athletics, and schools that fall into this category are allowed to give their students full-ride scholarships, just to play for them. This is not the case in the lower divisions of college sports, like Lehman College, which is in Division III. Third division athletics cannot provide these full-rides, yet misconduct still persists.

According to the NCAA, the top major violations in Division III are:

- Extra benefits (possible financial abatements)

- Consistent financial aid: related to athletics

- Consistent financial aid: unrelated to athletics

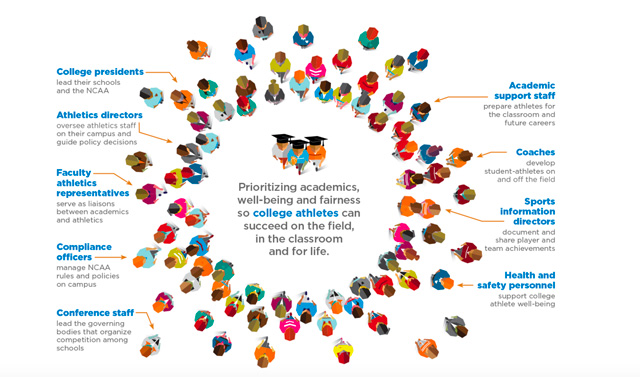

The NCAA says that its role is to provide oversight for college athletics but also to protect players. According to Zwiren, the NCAA is “too big to fail.” Much like the investment banks, there is no other organization ready to step in and govern college sports with over 90 different sports and three separate divisions.

Thus student-athletes are in a battle with the universities who they are playing for, and with the governing body that is ostensibly supposed to be protecting them.