En Garde: Fencers Face Off at Hunter

Hunter and CCNY Sabre fencers ‘touch’ simultaneously. No points awarded in this case.

By Luis Fonseca

Hunter College and its fencing team hosted the day-long Eastern Women’s Fencing Conference (EWFC) February 16. Johns Hopkins University won its second straight team championship, decidedly beating all its opponents and also won the individual championships.

The NCAA regional schools that participated were Drew University, Johns Hopkins University, Stevens Institute of Technology, Vassar College, Haverford College, Yeshiva University, City College of New York (CCNY) and Hunter College.

Coaches gathered around for pre-competition meeting. Linda Vollkommer-Lynch, tournament director, third from left.

Fencing dates back to Egyptian and Roman times and has seen many transformations in purpose, styles, and conventions. At this championship, the three weapons of fencing – foil, epee and saber were on display. In the team phase of the event, schools faced each other in a round robin format. Each team had up to three fencers per weapon and three rounds per fencer. The first fencer to reach five points in its bout won a point for the team. Nine points are the maximum possible per weapon, 27 points is the most per team. In the individual phase, 16 players battled in direct elimination format.

Coach Randy Bresil with fencers.

Coach of Hunter’s team, Randy Bresil, is a former fencer and alum of the school. He is now in his seventh season as the men’s and women’s fencing coach and has seen both teams make gradual progress. He and the other coaches face many challenges of this old, but now relative popular sport, in colleges (45 NCAA sanctioned, 160 college fencing clubs), not to mention hundreds of US clubs.

One of the most significant challenges is the fact that in the NCAA, unlike some of the more popular sports where teams play in their own D1, D2 or D3 divisions, fencing is played across the three divisions. So it is possible to have a D1 school such as Columbia go against Vassar a D3 school.

This can set up quite a disparity of skill and talent and can mean a lot of discouraging losses. “We need to keep their spirits up and do a lot of teaching,“ says tournament director Linda Vollkommer-Lynch, who is also EWFC founder and treasurer. Even within D3 schools there can be quite a difference in skill levels of fencers.

CCNY’s Katherine Langkamp just started this season as a senior and faced Vassar sophomore Zoe Tolbert, who has been fencing since she was 10. When Katherine’s mother was asked what if there was a downside to fencing, she replied, “None, except, she did not do more of it before.”

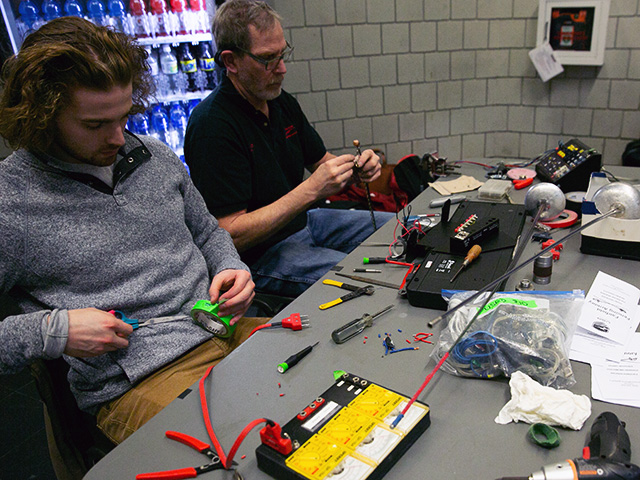

Fencing technology remains a challenge for coaches, fencers and referees alike. There are many moving pieces, from the tip of the weapon to the lamé, a jacket with metal threads, to the wires that run from the body to the foot of the strip, wireless score remotes, and the scoring mechanisms. Any glitch causes a delay and a change in tempo of a match. During the event, on-site fencing armorer Stuart Whiteside and his assistant tightened an epee’s tip and took apart the compartment that spools the wires that the fencers are attached to during the match.

Stuart Whiteside and assistant armorers, left, attending to the many repairs that arise when eight teams compete at the same time. Stevens fencers, right, unraveling wiring connections.

The sport is surging in popularity. Americans at the World Cup level and the Olympics are no longer the “whatever” team as VollKommer-Lynch put it. Americans are now finishing among the top teams and doing well in the individual competitions as well. Across the US, there are now programs, clubs, and schools for eight year olds and up. New attitudes to the sport are taking root. As the Haverford coach, Chris Spencer, notes “We run, do push-ups, do yoga, have them in the weight room three days a week, we plug them into athletics. Same work out as the basketball and soccer teams.”

Haverford coach Chris Spencer concerned as Spencer’s fencer executes unusual move against one if his fencers.

The head referee at the championship is Doc Rolando. He is a veteran referee and six-time fencing champion. “Referees used to be held at a very high regard, no talking to a referee, no questioning a referee,” he said. “Now, there is a lot of pressure from fencers, coaches and parents that want to gain an advantage they want to mess up the referee so they might get calls in their favor.”

Parents are investing a lot on the sport and as Rolando put it, “Tens of thousands of dollars in benefits to those families, if that kid does well. Not the case many years ago, now there is money to be had.” Yellow, red and unlike soccer, black cards are probably going to be more visible now, as well.

Stevens fencers, right, unraveling wiring connections.

The championship showed a balance between team spirit and individualism. Hopkins freshman, Alexandra Szewc, now in her fifth year of fencing said, as in individual sport it gives her more room to experiment. “I can do whatever I want to try, new things, new actions,” she said. Next to her, her mom quipped, “It is a lingo.” She suggests other parents have their children try fencing. She did acknowledge the cost, (at Hunter and other colleges, the school does supply the equipment) and the time commitment, but the cost of equipment is getting better.

Vassar’s Zoe Tolbert arguing with bout referee as CCNY coach, Paul Yuen, and his fencer, April Vargas, look on.

As a team sport, the bonds and support among the players were easy to see. Hugs and embraces of consolation, as well as, teams huddling and psyching themselves up, cheers, grunts and screams could be heard across the gym at any moment. High-fives and cheerful glances all around.

Hunter fencers

Saved under Entertainment, Featured Slide