Haitians Face Citizenship Dilemma

A protest outside the Dominican Republic’s embassy. (Photo: Haitian Diaspora for Civic and Human Rights)

By Laura Guerrero

With additional reporting by Anugya Chitransh

What do you do when you are trying to obtain a copy of your birth certificate, but the government no longer considers you one of its citizens? That is the question that many Dominicans of Haitian descent are now asking themselves after the Dominican Republic passed a new Constitution.

The 2010 Constitution, which came into effect immediately, says that “sons and daughters born to foreign-born members, as well as those who reside illegally on Dominican territory,” will not be granted Dominican citizenship. This is a radical change from the previous 2002 Constitution, which stated that all people born on Dominican territory, regardless of their parents’ legal status, were automatically granted citizenship.

The Dominican court has given the Central Electoral Board one year to come up with a list of all citizens whose status will be questioned, going so far back as to 1929. The ruling was met with considerable opposition in the Dominican Republic and in the United States. The United Nations human rights office said the change “may deprive tens of thousands of people of nationality, mostly all of Haitian descent.” The UN also said it will open a floodgate and that other countries will soon do the same.

On October 17, there was a protest outside the Dominican Consulate in New York. “Everyone has rights to live,” said Gerada Laurent, who has a brother and cousins currently living in the Dominican Republic. Because of this decision, she said, they would be sent back to Haiti. Activist Merritt Gelfand Claude recently adopted two Dominican girls. “They won’t have citizenship there now because they are originally from Haiti,” she said. Monique, a nurse, said Haitians would never do the same to their neighbors. “There are Dominicans in Haiti, too. We don’t have a problem with them.”

The University of Massachusetts’ Haitian Studies Association released a statement, calling the ruling an outrage. “The ruling violates several principals, including the due process of law to strip nationality rights from thousands of people without credible cause, the non-retroactive nature of law, and the rights of the child to identity and nationality.”

Aníbal de Castro, the Dominican ambassador to the U.S., defended the ruling in a letter to the New York Times, saying the Dominican Republic had a clear right to regulate immigration and that, unlike the U.S., it did not automatically confer citizenship upon those born on its soil. He disputed reports that the ruling will leave Haitian stateless. “The Dominican government is fully aware of the plight of the children of illegal Haitian migrants born in the country who lack identity documents…Haiti’s constitution bestows citizenship on any person born of Haitian parents anywhere in the world.”

He added that each case will be subject to judicial due process. “Speculation about mass deportations that I have heard is therefore baseless,” he said.

Ambassador Aníbal de Castro

Hundreds of thousands of Haitians could be impacted by the new legislation. Professor Milagros Ricourt, an associate professor of Latin American, Latino and Puerto Rican Studies at Lehman College, says the scope of the ruling was hard to fathom. “My mother was born in the Dominican Republic in 1929,” she says. “Her children, her grandchildren and her great-grandchildren (three generations) were already born in the Dominican Republic. Imagine if my mom had been born the daughter of a Haitian who was considered ‘in transit.’ Our Dominican citizenship would be stripped from us. This is completely insane.”

There is one small upside, says Ricourt, whose research focuses on Hispaniola and race/ethnic relations between Haitians and Dominicans. “The positive side to all of this is that the Constitutional Tribunal did not vote unanimously in favor. For the first time in history, there is a division in the Dominican Republic in regards to the Haitian issue. There were two members of the Constitutional Tribunal who flatly rejected this decision.”

Ricourt says that there are Dominicans who still believe in anti-Haitian discourse that they’ve been taught for generations. “It’s been said that ‘Haitians kidnap Dominicans’, and ‘Dominicans are enslaved in Haiti’, or ‘Haitians are witches’,” she says. “So many outrageous things.” She says that anti-Haitianism was in the Dominican Republic even before both countries existed, when both were still colonies of France and Spain. Adding insult to the injury, the new law was approved around September 23rd, a significant date for Haitians. “On this day, in 1937, the Haitian massacre was beginning,” Ricourt says, referring to “El Corte” as it is known by Dominicans. English texts call it The Parsley Massacre.

(Photo: Haitian Diaspora for Civic and Human Rights)

“Between 10,000 to 20,000, Haitians were killed from September 23rd to the beginning of October,” says Ricourt. “They were stabbed to death. Since there are some Dominicans who are also Haitian, people were asked to say perejil (parsley). In French, the ‘r’ is pronounced different than in Spanish. That is how the government was able to identify who was ‘Dominican’ and who wasn’t. Those who couldn’t say perejilthe right way, were killed. It was a genocide.”

Curiously enough, the same person who authorized The Parsley Massacre was also of Haitian descent. “Rafael Trujillo had Haitian blood,” says Ricourt. “His grandmother’s surname was Chevalier.” Three-term president Joaquin Balaguer had a grandmother of Haitian descent, too, she says. “The latest person to continue with this hatred toward Haitians is Leonel Fernandez,” says Ricourt another three-term Dominican president. “Ever since he came into power, he has continued with the Haitian deportations.”

(Photo: Haitian Diaspora for Civic and Human Rights)

Response in Dominican newspapers is divided, says Ricourt, pulling up a tally that she recorded based on comments posted in response to Juan Bolivar’s article “Se impone la solidaridad” on Acento, a Dominican digital newspaper. Bolivar’s opinion is that the ruling is unjust. Among those who commented in response to his article, 16 were in favor of the ruling, while 14 were against it.

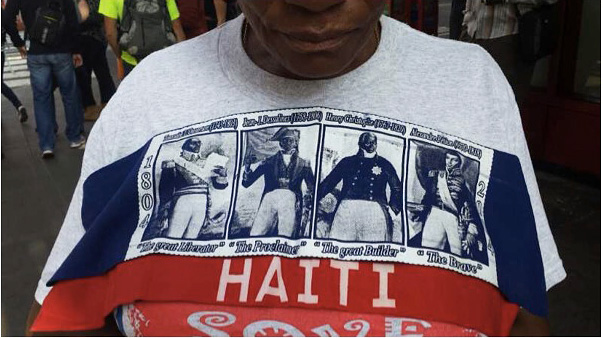

A protestor wears a T-shirt bearing the images of important Haitians in history. (Photo:Anugya Chitransh)

Saved under Featured Slide, News