Housing Justice, Housing Futures

Pictured from left to right: Elora Lee Raymond, Tela Troge, Jacqueline Paul Sims, Lisa Y. Lee, Akira Drake Rodriguez, and Oksana Mironova

By Ryan Pullido

New York City can be a brutal and unforgiving city. All it takes is one crisis to go from having everything to having nothing. And, as the city faces a housing crisis, many ponder where “Where do I go next?”

A collection of scholars, city planners, architects and activists gathered at Barnard College in February to discuss the housing crisis for the 48th Annual Scholar and Feminist Conference. The conference, with a theme of “Housing Justice/Housing Futures,” drew hundreds despite the cold weather.

According to the Population Reference Bureau, more than half of New Yorkers are rent-burdened or paying more than 30% of their income on rent. In addition, rent in New York has risen over 30% since 2015 and home prices have increased by 50% during the same period.

In parts of the Bronx – specifically Bronx Community Districts 9, 10, and 11 – nearly 55% of the current residents are already rent-burdened while 30% of them are severely rent-burdened. According to a June 2022 market report by real estate firm Douglas Elliman, the average price of co-ops and condos in Manhattan in the second quarter of last year was $2.1 million and the median was $1.2 million.

“Most people are one or two paychecks away from crisis,” said Miriam Neptune, senior associate director at the Barnard Center for Research on Women (BCRW) in her opening remarks. The COVID-19 pandemic proved this when it greatly impacted housing. According to usafacts.org, the price for an average home increased by 16% between April 2020 to April 2021. Not only that but there were many who lost their homes and were facing a crisis. According to the NYS Eviction Crisis Monitor, there were 143,094 eviction cases at the start of the pandemic, and this has continued to increase to the present day.

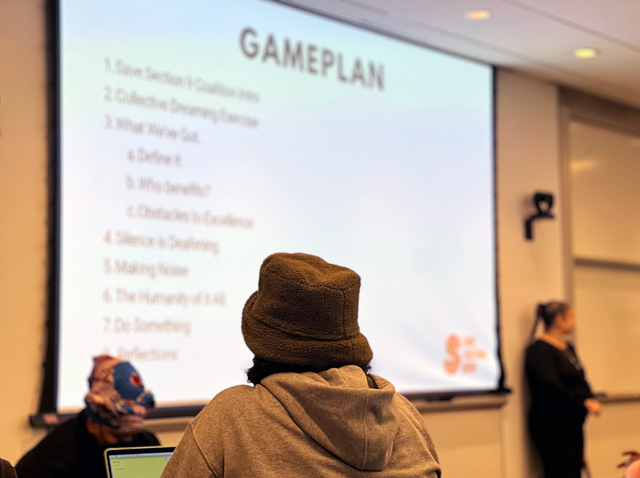

An attendee listening to the Save Section 9 Workshop.

For many, such as Teresa Scott, affordable public housing is the only thing that saved them from this crisis. The New York City Housing Authority, or NYCHA, is home to roughly 1 in 16 New Yorkers across over 177, 569 apartments. In addition, NYCHA serves over 339,900 residents in 162,143 apartments within 277 housing developments through the conventional public housing program

“Housing is what saved me,” said Scott, on the verge of tears. Scott discussed the importance of preserving affordable housing and saving Section 9 of the US Housing Act of 1937. This act mandates public housing as a federal program. She, along with the organization Save Section 9, continues to fight the privatization of homes and the “discriminatory disinvestment in America’s only truly affordable housing.”

The threat to Section 9 comes from the “Public Housing Preservation Trust” announced in 2020 as part of NYCHA’s Blueprint for Change. These are a series of plans that are aimed to improve NYCHA buildings as well as protect its residents. The trust will operate like a private management company and will have permission to privatize 25,000 units if these units are found uninhabitable. In addition to this, the trust also opens up the possibility of a future foreclosure and ending true Section 9 public housing in the city.

What does housing justice look like? This was one of the questions that echoed throughout the day. For some, it may be being able to afford the white picket fence house with a spacious backyard.

But for Christina Chaise, an advocate for Section 9 as well as a resident, it’s more than that. It’s the ability to have multigenerational housing and stop the privatization of public housing. It’s having robust tenant rights and protections and having rent capped at only 25% of your income. For her, that is true affordability and housing justice.

The fact that the fight for housing justice is long and tedious as proven by Tela Troge. As a member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation, she watched as most of their land was stolen from them. What were once Indian burial grounds were turned into mansions and playgrounds for rich billionaires. Ultimately, through donations from donors, they were able to reclaim parts of their land back and demolish the mansions that were built on their sacred grounds.

Despite the bittersweet victory, Troge does acknowledge that the concept of housing justice is complicated. She said that those mansions which were demolished could have been used as additional housing for members of the tribe. But, by the same token, that the mansion should not have been built there, said Troge, because it was sacred ground.

“We have to be students of history,” said Lisa Y. Lee, citing redlining and how it has affected housing in the United States. “We cannot go forward with building a better housing future without coming to terms with what happened in the past.”

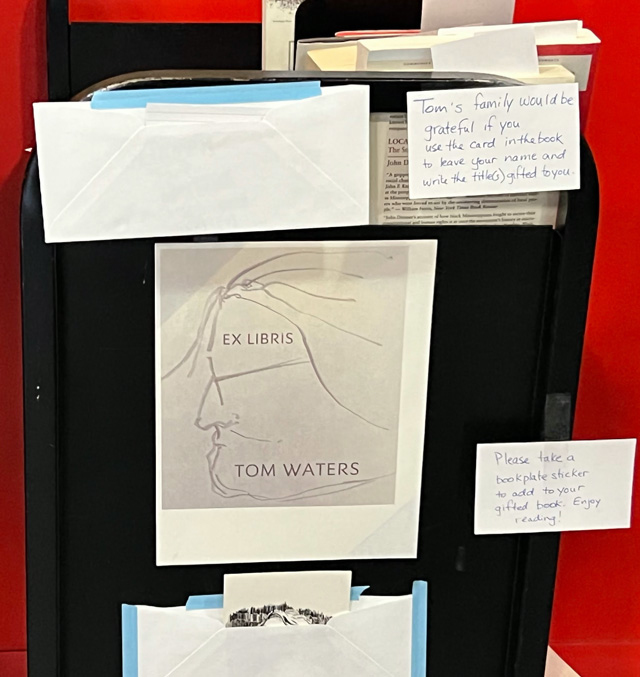

A book cart with free books to take for attendees to take along with a bookplate sticker of Tom Waters.

Saved under Featured Slide, News