Deep Roots of Black Hair Angst

By Brianne Glover

A lot of black hair journeys begin the same way: a little black girl, no older than four, and a ‘no lye’ relaxer kit. In that box is the key to being beautiful. I remember holding a well-known brand in particular “Just For Me” in my lap and staring at the pretty brown-skinned girls on the box. A coveted child hair relaxer, “Just For Me” often portrayed little black girls with long and shiny, amazingly straight hair. I wanted to look just like the girls on that box.

And when it came time for the box to be opened, I felt like it was a natural part of being black, sitting and having my scalp feel like it was on fire in order to have a better grade of hair. What I later learned through my own hair journey, and by the journeys of other black women, is that the internal struggle over what it means to be black and beautiful goes back way beyond our childhood years.

Hair is often seen as a direct representation of who we are and where we want to be socially. Just the other day I stood in line at Häagan Daaz behind a young black preteen, possibly biracial. The girl had long beautiful golden tresses and blue eyes. Her complexion was bright and fair. Her grandmother sat by as she ordered ice cream, lovely herself, only mocha colored. I couldn’t help but think to myself how lucky this girl was to have pretty hair and blue eyes. I found myself thinking, “She’ll never have trouble finding a boyfriend.”

Black girls like that I envy. Mostly because they have everything a black girl needs to be considered attractive. This preference for straight hair is far from new. It is a deeply ingrained idea, dating back centuries, that a black girl’s beauty depends on her hair. Tracy Patton wrote about the role hair played before and during slavery in her article “Hey Girl, Am I More Than My Hair?” Patton explains how enslavers realized the importance hair played in West African society and would shave the newly enslaved Africans’ heads to strip them of their prestige and identities.

Philiouse is one of the nine women who share their hair journeys. (See below)

Straighter hair was seen as a ticket to a better life. “Emulating White hairstyles, particularly straight hair, signified many things in the Black community,” Patton wrote. “Straighter hair was associated with free-person status.” According to Patton, this also meant a better chance at being freed once the plantation master died. All of this reinforces the idea that the straighter the hair, the better chance a black person had at thriving.

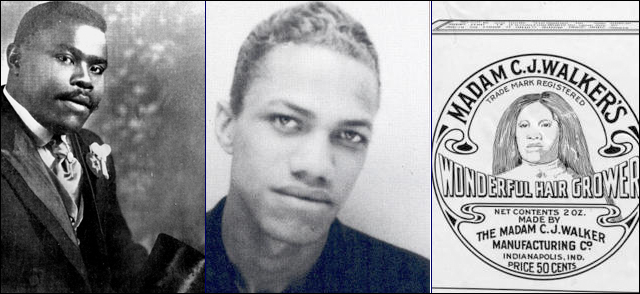

Of course not everyone agreed with the notion. Prominent figures such as Booker T. Washington, W.E.B DuBois, and Marcus Garvey, all believed that straightening one’s hair was, in a sense, selling out. Madame CJ Walker didn’t agree with these black leaders. She built an empire from hair straightening products. Walker believed it was a hairstyle, not a way of running from the past.

Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Madame CJ Walker product

The battle of hair continued on after slavery and into the civil rights movement. “Black is beautiful” initiatives pushed the agenda that there was no need to conform to white standards of beauty. When Malcolm X was younger, he chemically altered his hair using lye. This technique was called ‘conking’ and worn by many black men in the 1920s. Even though he chemically straightened his hair in his youth, Malcolm X prominently opposed hair straightening in later years, saying it reflected a culture ashamed of its diversity and uniqueness.

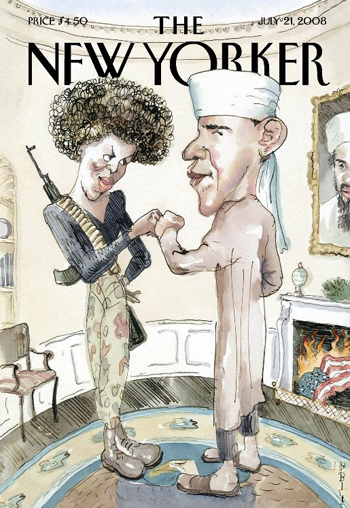

Militant Michelle

Moving pass the 60s to the present day, the black community sports many different hairstyles. Straightened hair, treated chemically or with heat, is still at the top of the list of styles. In my personal experience, black hair in its natural state is on the rise in women in their mid 20s. Leaving weave out of the equation and focusing mainly on chemically processed hair, and naturally occurring hair, one theme remains the same. As children, black girls learn early on that beauty means long, silky, flowing hair.

Moving pass the 60s to the present day, the black community sports many different hairstyles. Straightened hair, treated chemically or with heat, is still at the top of the list of styles. In my personal experience, black hair in its natural state is on the rise in women in their mid 20s. Leaving weave out of the equation and focusing mainly on chemically processed hair, and naturally occurring hair, one theme remains the same. As children, black girls learn early on that beauty means long, silky, flowing hair.

Little black girls are not alone in this thinking. There are plenty of cases of discrimination in the corporate world for ‘ethnic’ hairstyling such as braids, twists, dreadlocks, and afros. Unfortunately, these hairstyles are mostly worn the black community.

All this fuss over hair leads me to believe many see kinky hair as militancy and defiance instead of as just plain hair. A great example would be the cover of the 2008 ‘New Yorker’ magazine depicting the president and first lady in a satirical situation. If we look solely at how Michelle Obama is portrayed, wearing a military outfit, totting a gun, and strapped with bullets, you cannot fail to notice she is rocking an afro even though throughout the campaign her hair has been straight.

It is far from a coincidence. The afro equals defiance and upheaval. This view is deeply engraved into the minds of blacks and whites alike and may stem from the 60s and the Black Panther movement.

Ayana Byrd and Lori Tharps, authors of the book “Hair Story,” found that the black community spends $225 million annually on hair weaving services and products. Most of these “black products” are not manufactured or owned by the black businesses. The comedian Chris Rock gave America a small peek of what this multimillion-dollar industry is about. In his documentary “Good Hair,” Rock explores the culture behind weaves and how much money is spent on hair in the black community. However, Rock did not delve deep enough into the effects the media truly has on young black girls. Rock also touched only lightly on black girls struggles with their naturally occurring locks.

Singer India Arie wrote the song “I Am Not My Hair” not just for black women, but all women. However, the first few lines of the song depict Arie’s struggle with her hair identity over time.

Why should you care? Technically this only affects 12 percent of the population right? Wrong. Even if a person does not have kinky or curly hair, they may have feelings and associations with it. What I find unsettling is the lack of awareness of the issue. That is, of course, until a little brown skin muppet sang on Sesame Street about her hair.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cz5nlr8oujA

Jenee Darden, a reporter, interviewed the writer of the Sesame Street song in this piece, Empowering his Daughter.